|

|

Vol.

27 No. 4

July-August 2005

| IUPAC Wire |

| |

News and information on IUPAC, its fellows, and members organizations

See also www.iupac.org/news |

Honoring A Hero

A Letter from Oliver Sacks

I was delighted to read in the January-February 2005 issue of Chemistry International that IUPAC (at last!) approved a name for element 111—and especially that the new name honors a great hero of mine, [Wilhelm Conrad] Roentgen. I think that Roentgen too would be pleased by this, though he was the most modest of men, too modest even to go to Stockholm when he was awarded the first Nobel Prize in physics.

|

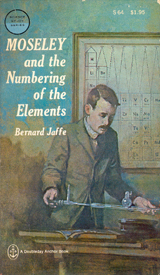

| Moseley and the Numbering of the Elements, by Bernard Jaffe, was published in 1971 by Doubleday and Anchors Books as part of their Science Study Series. The book traces Moseley's brief career in the context of the most exciting years of discovery in the 1910s, when scientists such as J.J. Thomson, Ernest Rutherford, Hans Geiger, and Niels Bohr set the stage for the nuclear age to come. Jaffe, just about 10 years younger than Moseley, had a long career himself as a science writer. He died in 1996 at the age of 90. |

Prior to the 1940s there were only two elements with names honoring scientists—the rare-earth elements samarium and gadolinium (Samarski was a mining engineer, Gadolin was a chemist)—though other names (davyum, scheelium, etc.) had been proposed over the years, but dropped. When the highly radioactive transuranic elements started to be created there was a strong move, starting with curium (element 96), to honor the pioneers of the new age with their names. So, curium was followed by einsteinium (99), fermium (100), mendelevium (101), lawrencium (103), rutherfordium (104), seaborgium (106), bohrium (107), and meitnerium (109). Though one might expect chemical elements to be honored by the names of chemists, only Mendeleev and Seaborg, of the above group, were primarily chemists. (It is true that Rutherford was given his Nobel Prize in chemistry, but this aroused his amusement because he was, and considered himself, a physicist, and had little respect for other sciences: If science was not physics, he once said, it was only “stamp-collecting.”) Marie Curie, of course, got Nobel Prizes in both chemistry and physics, and her final isolation of radium was a marvel of applied chemistry.

One wonders who will be chosen when the elements from 112 on are finally given approved names by IUPAC. Two names immediately come to mind—names of great pioneers from the heroic early years of the twentieth century when so many new elements were being discovered and the Periodic Table was completed, at least in principle, up to uranium. One such pioneer was Frederick Soddy, who worked with Rutherford in their crucial years in Montreal, defining new radioactive isotopes and their pathways of decay. (It was Soddy who coined the word “isotope,” and in 1921 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry.) The other is Henry Gwyn Jeffreys (Harry) Moseley, the dazzling young theoretical physicist who worked out the real meaning of atomic numbers, and then, in principle, completed the Periodic Table by predicting the existence of elements 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87, and 91, stressing that these, and these alone, remained to be discovered. He thus, in Soddy’s phrase, “called the roll of the elements.” (Moseley was killed, tragically, at Gallipoli, in 1915—he was only 27, and there is no saying what he might have achieved had he lived.)

Oliver Sacks, author and neurologist, has had a life-long interest in the sciences and a fascination with the periodic table. In his recent memoir, he invokes his childhood in wartime England and his early scientific fascination with light, matter, and energy as a mystic might invoke the transformative symbolism of metals and salts. The "Uncle Tungsten" of the book's title is Sacks's uncle Dave, who manufactured light bulbs with filaments of fine tungsten wire, and who first initiated Sacks into the mysteries of metals.

www.oliversacks.com

Page

last modified 17 June 2005.

Copyright © 2003-2005 International Union of Pure and

Applied Chemistry.

Questions regarding the website, please contact [email protected]

|